The power of sameness

Individualism in the algorithmic era

Rugged individualism is the brand of America and arguably the ideological engine behind global capitalism. It fuels consumerism, branding, and increasingly, the personalization of everything. From algorithmic feeds to bespoke products, the promise is clear: you are unique, and we will cater to your uniqueness.

This myth of the special has consequences. It drives hyper-specialization, tribalism, and a fractures our sense of self. It also obscures a deeper truth, that we are far more similar than we care to admit.

Individualism as cultural infrastructure

Individualism has long been the scaffolding of branding. From Marlboro Man to Nike’s “Just Do It,” the message is thus: stand apart, be different. Win your identity.

As markets evolved and complexity kept on growing, so did roles. New functions emerged to meet niche demands, reinforcing the idea that being “special” means being valuable.

Specialism means having cliques of staff that speak different languages trying to work together. Technical, operational or conceptual languages. This specialist hierarchy - a pecking order - makes co-operation and collaboration increasingly laborious.

Personalization at scale, or the ‘datafication of identity’, underpinned by surveillance marketing, has turned individuality into a commodity. A data point. Algorithms engineer difference, then guide people toward the perceived safety and familiarity of echo chambers.

The absurdity and parody of mass individuality

Whilst iconic science-fiction writers focused on high drama futures, be they dystopian or operatic, only David Foster Wallace captured the banality of an attention-focused world in “Infinite Jest”.

He warned of the existential trap of hyper-individualism: a culture where everyone is the protagonist, yet no one connects. His critique aligns with sociologists Zygmunt Bauman and Ulrich Beck, who saw neoliberalism as a system that isolates under the guise of freedom, or “perfection without the connection” as the Economist recently described AI’s role as a digital wingman.

Mark Ritson critiqued hyper-targeting in marketing. He argued for less segmentation, suggesting that big, resonant ideas can galvanize broader audiences more effectively than atomized 1:1 messaging. Yet, personalisation at scale appears unstoppable.

The psychology of sameness

It’s evolutionary fact.

We evolved in cooperative groups, not in perpetual conflict. “Too many scholars and popular voices remain committed to the view that the evolution of humanity has been, in large part, driven by the patterns of in-group cohesion and out-group conflict. They are wrong. The majority of current research into humans and our history refutes the idea that deep-seated xenophobia is the central factor in human evolution.” (Agustin Fuentes)

It has been mathematically tested.

In game theory the “tit-for-tat” strategy - cooperate first, retaliate only when necessary - is the most successful in iterated prisoner’s dilemma scenarios. Game theory, while mathematically rigorous is challenged in application to real-world scenarios, because it is built on assumptions that simplify humans. Even so, the impacts of cooperation are clear.

Neuroscience sheds new light on conforming and deviating behaviors.

Studies have come a long way since Solomon Asch developed his famous experiments on social pressure in the 1950s.

“We see conformity as a weakness; we say it supports bad behavior, but if you think conformity is a powerful social mechanism through which we change our ideas about the world, it could be used positively.” (Jamil Zaki). It’s clear that people gravitate toward those with similar values to reduce psychological discomfort and cognitive dissonance.

“We did not evolve to be us versus them.”

Science-fiction, the hive mind, and the cosmic horror of sameness.

Science fiction often portrays the hive mind as dystopian; an enemy of freedom and individuality. In books like Brave New World and 1984, the collective is seen as oppressive, echoing Cold War fears of communism.

H.P. Lovecraft was one of the most influential writers of the 20th century. His paranoia and xenophobia led to some of the most powerful and terrifying articulations of the unknown and the other.

Yet earlier depictions, for example H.G. Wells’ The First Men in the Moon or even Asimov’s Foundation series imagined hive minds as empathetic and hyper-intelligent, even proposing them as the natural conclusion of humanity becoming an interstellar race.

The shift toward negative portrayals of sameness heralded the rise of consumerism and the commodification of identity.

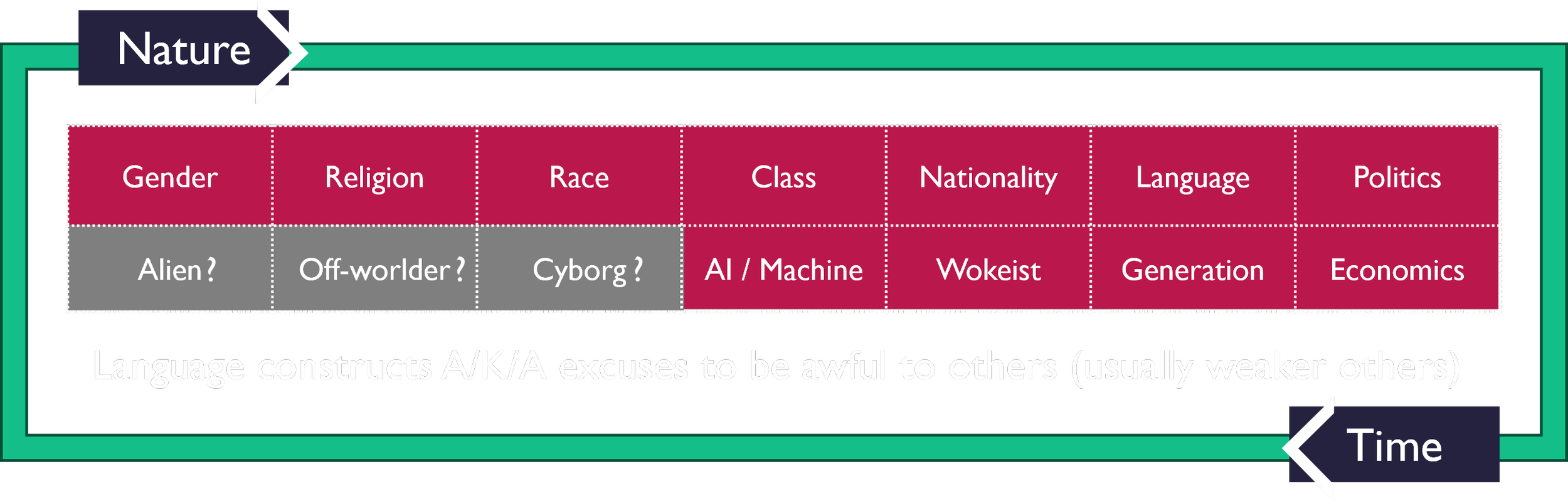

Otherness has been used for the purposes of conflict and conquest, the breaking point between progressiveness and conservatism, since time immemorial. The concept of "the other" has deep philosophical roots, best represented in Hegel's "Master-Slave Dialectic". True emancipation for the other - or lack thereof - was further explored by thinkers like Simone de Beauvoir, Angela Davis and George Orwell.

In 1972 Ursula K. Le Guin, wrote “The Word for World Is Forest” . It is a searing indictment of otherness based on man’s history of violence toward other men labelled as “savages”. On Athshe, a native population of forest-dwelling, dream-focused people is exploited by Terran colonists from Earth who strip-mine the planet's timber for their dying world.

Spoiler alert: they are all distantly related humans - a long-forgotten human interstellar civilisation settled multiple planets and their inhabitants evolved. Widely viewed as the inspiration for James Cameron’s Avatar, not Dances With Wolves (1988).

Chris Morris, in works like Brass Eye and The Day Shall Come, satirises how media constructs “the other” to justify persecution. Otherness becomes a tool to polarize in politics, to sell in business and to simplify in media.

Black Mirror uses the concept of otherness to critique our societal tendencies to categorize, judge, and ultimately dehumanize those we perceive as different.

Wokeness is one such example of contriving otherness to extremes - Hollywood, plant-based food, LGBTQ+, diversity, are all attributes of so-called progressive agendas labelled as otherness to incite and inflame conflict far beyond what is really happening.

How businesses can harness sameness

Rather than fixating “solving complexity” through uniqueness and specialties, businesses can leverage sameness to build resilient, inclusive systems. Don’t consider conforming and deviating as mutually exclusive, but as mutually reinforcing, for betterment and sustained growth.

Consider a new consensus between coherence and independence, of systems and stories. You cannot benefit from one, without the other.

The core of the business needs to be coherent, teams and systems functioning properly through cooperation and collaboration, in service of efficiency and profit. A business also needs to harness deviation and independence, in service of innovation and competitive growth.

This consensus is built on our concept of cultures of enthusiasm, which are in turn built on six characteristics of businesses that outperform their peers. Companies with highly engaged teams deliver 21% greater profitability according to Gallup.

Common Languages:

Don’t reject, adopt and experiment with proven systems in areas like human-centred design, open-source and innovation. These help to bring together specialists and breakdown business language barriers.

Calculated Independence:

Don’t re-org, re-design to reflect a more nuanced view of contribution. Orient staff autonomy toward whether they are part of more centralised business coherency or more decentralised business divergence.

Integrated Measurement:

Don’t measure impact in isolation, recognize intangible and personal impacts. Systemise self-interest with group-interest to realise the benefits of cooperation and collaboration.

Communities & Tribes:

Can be great for bridging siloes. Done wrong they create another silo. Bring together different but related experts and invest effort in getting them to work on real cross-functional initiatives, ensure what they produce makes it out into the wider organisation.

Outcomes-based models:

Don’t burden BAU processes. Don’t merge processes into monolithic ones. Identify shared outcomes between teams first and then identify inflection points in their respective processes, that will improve those outcomes.

Similarity isn’t about leveling everything down, sacrificing feature-richness or diversity. The goal in design and product design is to harmonise only where it adds value to the person’s experience.

The power of sameness isn’t about erasing difference, it’s about recognizing our shared cultural architecture.

It’s a conscious process to find common ground, rather than a compulsive reaction to seek familiarity and exclude others.

Common ground creates the solidity needed to pursue original thinking and building more Lovable Products. Because in a world obsessed with standing out, perhaps the most radical act is to stand together.

© 2025 Oliver Spalding. All rights reserved. HITMXE® is a registered trademark of Oliver Spalding.

This post is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution. You may share this content with attribution, but not modify or use it commercially without written permission.